Some friends and I were discussing the Civil War the other day—a common topic. The subject came up, when did the war end? “On April 9, 1865, of course, when Lee surrendered to Grant,” said one. “No,” said another, “when Jo Johnston surrendered to Sherman in North Carolina.” “No, No, you’re both wrong,” said a third, “it was in Texas in May.”

“You’re all wrong,” said I. “The last Confederate troops to lay down their arms weren’t any of those. It was the Confederate Navy that was the last to surrender, or at least two of their ships.” And therein hangs a curious little tale or two.

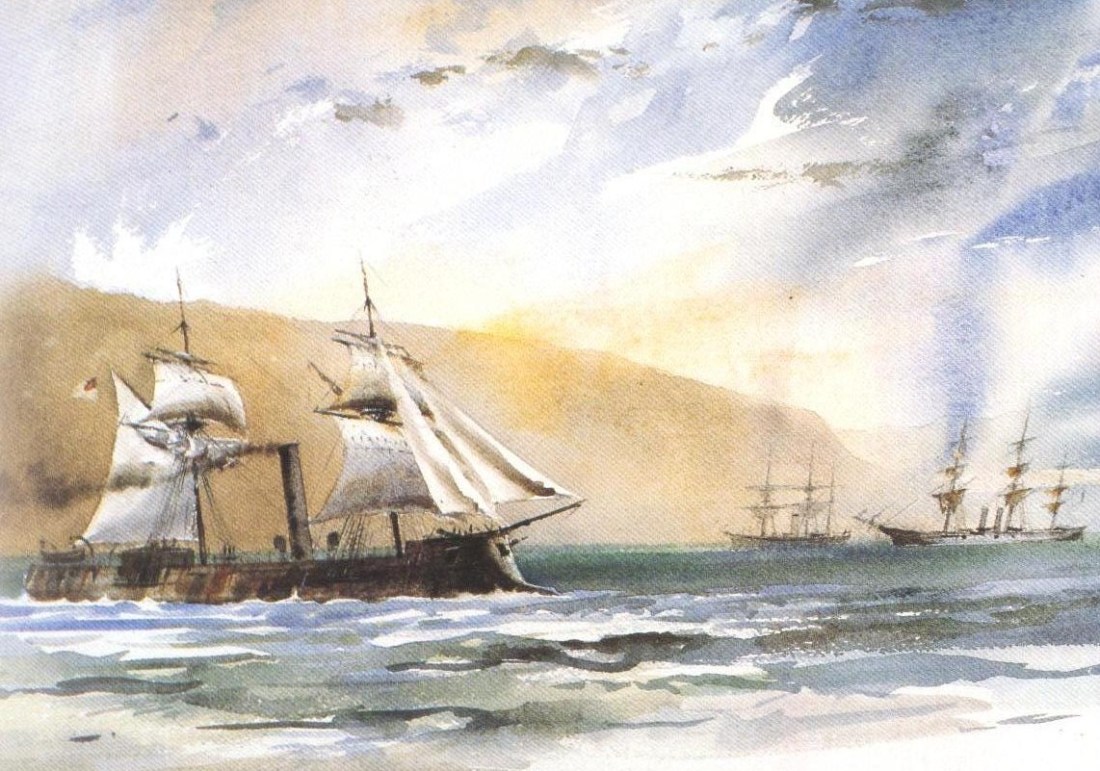

There was the CSS Stonewall, for example, a steam powered ironclad, built in France for the Confederacy. Napoleon III, who was eager to support the Confederacy and have access to their cotton crops, secretly authorized the construction of this powerful warship.

The U.S. government found out, however, so the ship was quietly transferred to Denmark where the ironclad finished being fitted out. It was there where Captain T. J. Page was made skipper of the new ironclad. It was a formidable warship, built in the style of the French “Ocean Class” warships and was one of the most powerful for its time: it boasted one 300 pounder main gun, with two 70 pounder guns in a turret on the aft deck, sheathed in thick steel armor proof to just about any cannon fire, as well as a powerful steel ram attached to the bow of the ship. The main gun fired forward, while the 70 pounders were in the turret, which presumably revolved, although it had a limited field of fire. The turret was handicapped by being located behind the aft mast instead of amidships, where the mast’s rigging seriously interfered with its line of fire. In addition, she was equipped with at least two Gatling guns on top of the turret.

Upon commissioning, it traveled down the European coastline, first to Brittany, thence to Spain and Portugal, with Yankee ships following at a respectful distance.

This powerful warship next cruised across the Atlantic and plied about the Caribbean for a bit, perhaps contemplating a raid or two against Union shipping.

Then one day in May, 1865, the CSS Stonewall showed up in Havana harbor, its solid steel sides and big guns looking quite intimidating. The US Consul in Havana nearly had a fit; he knew the Stonewall was impervious to anything the US Navy could throw at it; the Navy’s low-lying ironclad monitors were no match for it: the ram-equipped Stonewall could simply crush them beneath its armored prow. The commander of the East Gulf Blockading Squadron, Admiral C. K. Stribling, dispatched a detachment of warships to deal with the Rebel dreadnaught—although if the Confederates decided to make a fight of it, the Navy’s ships were likely doomed. However, Stribling sent a personal note to the captain offering generous terms of surrender. Captain Page, knowing that the Lost Cause was indeed lost, sold the ship to the Spanish governor of Cuba, paid off his crew with the money and he and his crew quietly made their exit from the scene. The Spanish then re-sold the vessel to the U. S. government for what he’d paid the Confederate captain.

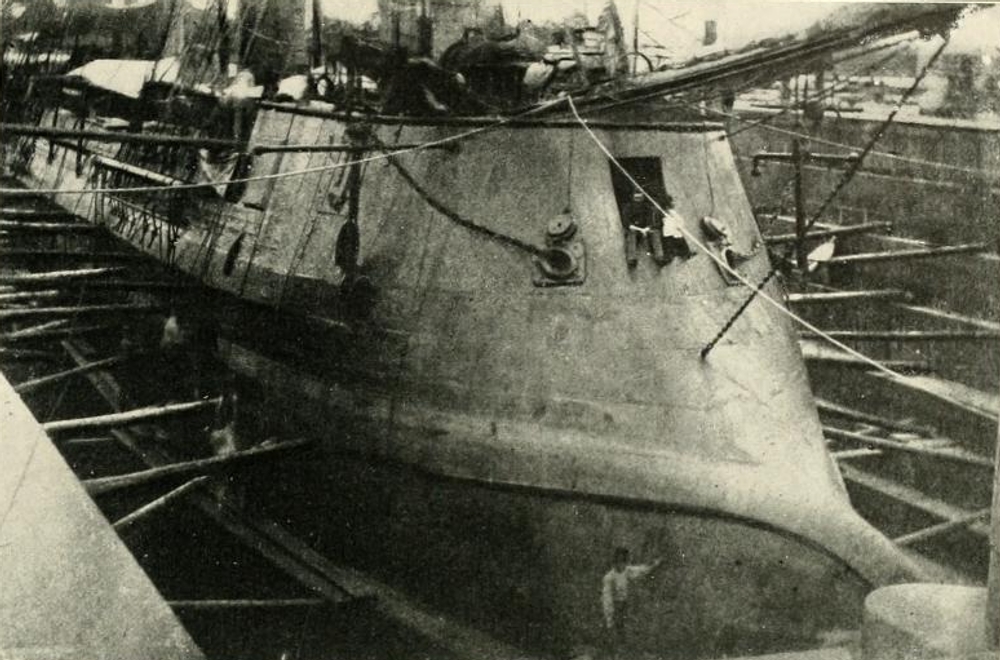

The Stonewall could lay fair claim to being the first modern battleship to see combat—but not with the Confederate Navy. After languishing in a Navy yard for a few years, the Stonewall was sold to the Japanese government in 1868, then busily modernizing its armed forces and in a hurry to catch up with the European powers. Initially, it was to be sold to the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan’s last vestige of its Feudal heritage.

However, factions in Japan pushing hard for modernization sought to revive Imperial rule and overturn the old feudal order and instituted a coup, of sorts, called the Meiji Restoration. But old ways die hard in Japan and their restoration of Imperial rule sparked a brief Civil War, The Boshin War. Remaining neutral, the US refused to hand over the Stonewall, now called the Kotetsu, which was briefly reflagged as an American vessel again.

Finally, in February, 1869, she was handed over to the new Meiji government, who named her the Kotetsu and promptly sent her north to Hokkaido to stamp out the last of Shogun resistance to the new regime. The Kotetsu participated in the Battle of Miyako , repulsing a rebel boarding party with its Gatling guns. The Kotetsu would go on to also fight in the Battle of Hakudate before the last remnants of the old regime on Hakkaido were finally defeated. In 1871, the Stonewall was again renamed, this time the Azuma, under which she remained in service until 1888 and was finally scrapped in 1908.

The Stonewall/Kotetsu was not the Rebel Navy’s last ship to lower its flag; but more about that next time.

- For hobbyists, there is in fact a model available of the Kotetsu, as well as a paper model of the Stonewall–a modeling specialty popular in Japan and Europe, not so much here. One enterprising Italian hobbyist used the scale plans from that kit to make a 1/75 scale wooden model.

My latest book about the Civil War is now in print and available: Ambrose Bierce and the Period of Honorable Strife, chronicling the war career of the famous American author and his war experiences in the Union army.