“JUNE 23, 1863, ended the Army of the Cumberland’s six months of wearisome inaction around Murfreesboro its half-year of tiresome fort-building, drilling, picketing and scouting. Then its 60,000 eager, impatient men swept forward in combinations of masterful strategy, and in a brief, wonderfully brilliant campaign of nine days of drenching rain drove Bragg out of his strong fortifications in the rugged hills of Duck River, and compelled him to seek refuge in the fastnesses of the Cumberland Mountains, beyond the Tennessee River.” John McElroy

So Civil War veteran and humorist, John McElroy, summarized one the greatest, yet least studied, Union victories of the War.

McElroy, the creator of the classic Si & Shorty series, the Civil War equivalent of Bill Mauldin’s WW II Willie & Joe, had seen frontline service and created his fictional alter ego as an everyman to describe what the war was like for the average enlisted man. In his multi-volume collection of stories, he chronicles the career of his “GI Joe” with the Army of the Cumberland. I cite McElroy in this context because he devotes a whole volume to the Tullahoma Campaign, which has traditionally been given short shrift by historians and novelists alike.

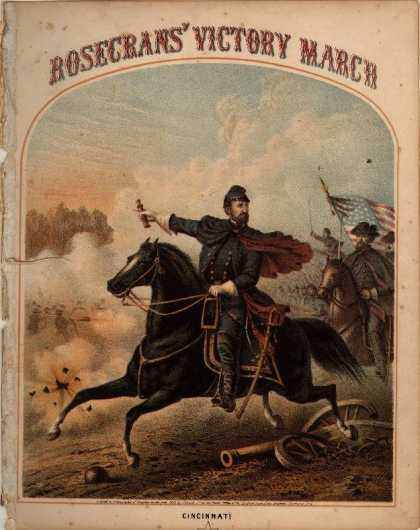

Even as the Army of the Potomac was desperately trying to stop Lee’s invasion of western Pennsylvania at Gettysburg and Grant’s long siege of Vicksburg was finally coming to an end, General William Rosecrans unleashed his well-planned and meticulously prepared offensive to drive the Confederate Army of Tennessee out of their well-prepared defenses.

General Bragg, better at planning than campaigning, had constructed a strong line of fortifications centered on Shelbyville, stretching to Columbia on the west and anchored on Tullahoma on the east, where the rail-line led south-eastward towards Chattanooga. As a further impediment, between the Union positions and Bragg’s fortifications stretched a series of rugged hills screening his army, with only a limited number of narrow and easily defended passes available to go through to attack Bragg’s entrenched army. Breaking through the Confederate defenses promised to be a long and bloody process, with limited chance for success.

Instead of a ponderous advance which would inevitably turn into a grinding and slow slugfest, Rosecrans resolved on a series of raids and feints against the outer Rebel lines on the western flank, to draw off the enemy’s reserves, followed by a massive left hook around the Confederate right, with view to seizing the Railroad and punch his way southward towards Chattanooga.

Before daylight on June 23, 1863, Union General Stanley’s mounted troops, supported by General Granger’s Reserve Corps, began their maneuvers against the western passes leading towards Shelbyville. In their efforts to seize these passes, the Federals had a secret weapon: Wilder’s Lightening Brigade. They were not cavalry but mounted infantry, who rode to battle and fought on foot. They were specially equipped with the new Spencer repeating rifle and could fire off seven volleys without having to reload, in effect giving the unit the firepower in combat of a division or even a small corps. In forcing the passes and other special missions, Wilder’s men proved their worth many times over.

Rosecrans three regular infantry corps were intended to be the main blow, ascending the Barrens to the east, then swinging around and hit Bragg in the flank and rear. Once the trap had been sprung, Rosecrans planned to use his infantry to deliver the finishing blow. At least that was how he planned it.

In the actual event, things did not quite come off as Rosecrans had hoped. While Wilder’s brigade forced their way through Hoover’s Gap and out onto the plains below, the complex maneuvers which each part of Rosecrans army were expected to execute were severely handicapped by nine days of nearly continuous torrential rain, slowing down the advance. Small creeks became raging torrents and the army’s mules pulling the supply wagons–never known for their adherence to orders–became doubly obstinate in the face of deep mud and swollen streams.

While the Rebels were initially surprised and rushed troops to defend the western passes, the rain-slowed pace of the Yankee maneuvers allowed Bragg to get some inkling of what the Yankees were up to before the jaws of Rosecrans pincers finally closed.

Despite the difficulties, however, Rosecrans’ men out-fought and out-maneuvered the Rebel army. The Union success was also aided at times by the insubordination of Bragg’s own subordinate generals, who had a tendency to ignore their commander’s orders whenever they felt like it. As Napoleon remarked about British cavalry, one could well say that the Army of Tennessee was, “the noblest and most poorly led.”

Had the rain not slowed the advance of the Army of Cumberland, Rosecrans’ plan to cut off Bragg’s retreat and defeat him in a battle of annihilation might have succeeded and eliminated the second largest Confederate army right then and there.

After what seemed endless miles of swampy roads and rain engorged creeks, fighting and maneuvering all the way, the Federal infantry approached the outer defenses of Tullahoma. It was assumed that Bragg would make his stand there. But as the lead elements forced their way through the jumble of branches and brush of the abatis outside the earthworks and then scrambled over the Rebel parapets, they found the enemy already gone and in the distance they could see the last bridge over the Elk river going up in flames behind the retreating Butternuts.

Bragg did not stop after crossing Elk River, however; he retreated over the Cumberland Mountains and across the Tennessee River, abandoning all of Tennessee and its valuable resources to the Federals.

The 4th of July dawned bright and cheerful for the troops under Old Rosy’s command, if not materially, at least in spirit, and the men of his regiments felt a surge of patriotic pride in their commander and in themselves for their accomplishment. And as the supply wagons finally caught up with the regiments, the Si’s and Shorty’s of the army could once again sleep under a blanket and enjoy a hot cooked meal.

“That night by its cheerful campfires the exultant Army of the Cumberland sang from one end of its long line to the other, with thousands of voices joining at once in the chorus, its song of praise to Gen. Rosecrans, which went to the air of “A Little More Cider.”

Cheer up, cheer up, the night is past,

The skies with light are glowing.

Our ships move proudly on, my boys,

And favoring gales are blowing.

Her flag is at the peak, my boys,

To meet the traitorous faction.

We’ll hasten to our several posts,

And immediately prepare for action.

Chorus:

Old Rosey is our man.

Old Rosey is our man.

We’ll show our deeds where’er he leads,

Old Rosey is our man.

By rights, General Rosecrans ought to have received equal adulation from his superiors in Washington as he did from the troops under his command. But instead of praise and commendation for having roundly whipped a formidable foe with only minor losses in a campaign carried out under the most trying of circumstances, Rosecrans received what seemed almost a rebuke from Secretary of War Stanton:

“Lee’s Army overthrown; Grant victorious. You and your noble army now have a chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion. Will you neglect the chance?”

Rosecrans’ ire and sarcasm in his response to Stanton can be sympathized with given the circumstances:

“Just received your cheering telegram announcing the fall of Vicksburg and confirming the defeat of Lee. You do not appear to observe the fact that this noble army has driven the rebels from middle Tennessee….I beg in behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.”

Rosecrans victory had been achieved in nine days: Grant’s achievement had taken months and only been won by attrition not combat. And while General Meade and his army had repelled a dire threat to the North at Gettysburg, and suffered tremendous casualties doing it, in the end Gettysburg was a purely defensive battle. Lee had not been defeated in open combat or forced to retreat in disarray as Bragg was, and Lee’s withdrawal southward was a leisurely affair, with Meade’s men following at a respectful distance. Yet both those victories then, and to this day, have overshadowed Rosecrans’ Tullahoma Campaign.

Military experts who have taken the time to analyze it have declared that “the Tullahoma Campaign was strategically more important than Gettysburg and tactically superior to Vicksburg” and that it marked “the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.” Another historian has described it as “a military masterpiece which did more damage to the Confederate cause than did Vicksburg or Gettysburg, and at very little human cost.” The Tullahoma Campaign resulted in the Federal army knocking at the door to the Confederate heartland. Rosecrans next move would be to swing that door wide open.

For more about the Civil War in the Western Theater, read Ambrose Bierce and the Period of Honorable Strife, Univ. of Tennessee Pres.