Christmas 1864. Richmond. Christmas is traditionally a celebration of abundance and cheer; but as Charles Dickens pointed out in his famous Yuletide tale, for many it can also be a time of want, need and hunger.

The South had seceded to much jubilation and overweening confidence—some would say arrogance. They would lick the Yankees in a few months it was boasted, and then the Confederacy would be a proud, independent nation and everyone would live happily ever after—except the slaves, of course. But by Christmas of 1864, that confidence had waned drastically, with Richmond under siege and Southern forces in retreat on all fronts.

The following memoir was written by Varina Davis, the wife of former Confederate president, Jefferson C. Davis. She contributed it to a newspaper in that hotbed of Secessionism, New York City, in 1896. While she had the advantage of hindsight, it is nonetheless enlightening as to conditions in the Confederate capital during the last Christmas of the War. So be your Christmas merry or morose, may this serve as a reminder of how the once proud overlords of King Cotton South– and the “mudsills” who had made their wealth possible– managed during that last winter of the Civil War:

“…Rice, flour, molasses and tiny pieces of meat, most of them sent to the President’s wife anonymously to be distributed to the poor, had all be weighed and issued, and the playtime of the family began, but like a clap of thunder out of a clear sky came the information that the orphans at the Episcopalian home had been promised a Christmas tree and the toys, candy and cakes must be provided, as well as one pretty prize for the most orderly girl among the orphans. The kind-hearted confectioner was interviewed by our committee of managers, and he promised a certain amount of his simpler kinds of candy, which he sold easily a dollar and a half a pound, but he drew the line at cornucopias to hold it, or sugared fruits to hang on the tree, and all the other vestiges of Christmas creations which had lain on his hands for years. The ladies dispersed in anxious squads of toy-hunters, and each one turned over the store of her children’s treasures for a contribution to the orphans’ tree, my little ones rushed over the great house looking up their treasure: eyeless dolls, three-legged horses, tops with the upper peg broken off, rubber tops, monkeys with all the squeak gone silent and all the ruck of children’s toys that gather in a nursery closet.

Makeshift Toys for the Orphans

Some small, feathered chickens and parrots which nodded their heads in obedience to a weight beneath them were furnished with new tail feathers, lambs minus much of their wool were supplied with a cotton wool substitute, rag dolls were plumped out and recovered with clean cloth, and the young ladies painted their fat faces in bright colors and furnished them with beads for eyes.

But the tug of war was how to get something with which to decorate the orphans’ tree. Our man servant, Robert Brown, was much interested and offered to make the prize toy. He contemplated a “sure enough house, with four rooms.” His part in the domestic service was delegated to another and he gave himself over in silence and solitude to the labors of the architect.

My sister painted mantel shelves, door panels, pictures and frames for the walls, and finished with black grates in which there blazed a roaring fire, which was pronounced marvelously realistic. We all made furniture of twigs and pasteboard, and my mother made pillows, mattresses, sheets and pillow cases for the two little bedrooms.

Christmas Eve a number of young people were invited to come and string apples and popcorn for the trees; a neighbor very deft in domestic arts had tiny candle moulds made and furnished all the candles for the tree. However the puzzle and triumph of all was the construction of a large number of cornucopias. At last someone suggested a conical block of wood, about which the drawing paper could be wound and pasted. In a little book shop a number of small, highly colored pictures cut out and ready to apply were unearthed, and our old confectioner friend, Mr. Piazzi, consented, with a broad smile, to give “all the love verses the young people wanted to roll with the candy.”

A Christmas Eve Party

About twenty young men and girls gathered around small tables in one of the drawing rooms of the mansion and the cornucopias were begun. The men wrapped the squares of candy, first reading the “sentiments” printed upon them, such as “Roses are red, violets blue, sugar’s sweet and so are you,” “If you love me as I love you no knife can cut our love in two.” The fresh young faces, wreathed in smiles, nodded attention to the reading, while with their small deft hands they gined the cornucopias and pasted on the pictures. Where were the silk tops to come from? Trunks of old things were turned out and snippings of silk and even woolen of bright colors were found to close the tops, and some of the young people twisted sewing silk into cords with which to draw the bags up. The beauty of those home-made things astonished us all, for they looked quite “custom-made,” but when the “sure enough house” was revealed to our longing gaze the young people clapped their approbation, while Robert, whose sense of dignity did not permit him to smile, stood the impersonation of successful artist and bowed his thanks for our approval. Then the coveted eggnog was passed around in tiny glass cups and pronounced good. Crisp home-made ginger snaps and snowy lady cake completed the refreshments of Christmas Eve. The children allowed to sit up and be noisy in their way as an indulgence took a sip of eggnog out of my cup, and the eldest boy confided to his father: “Now I just know this is Christmas.” In most of the houses in Richmond these same scenes were enacted, certainly in every one of the homes of the managers of the Episcopalian Orphanage. A bowl of eggnog was sent to the servants, and a part of everything they coveted of the dainties.

At last quiet settled on the household and the older members of the family began to stuff stockings with molasses candy, red apples, an orange, small whips plaited by the family with high-colored crackers, worsted reins knitted at home, paper dolls, teetotums made of large horn bottoms and a match which could spin indefinitely, balls of worsted rags wound hard and covered with old kid gloves, a pair of pretty woolen gloves for each, either cut of cloth and embroidered on the back or knitted by some deft hand out of home-spun wool. For the President there were a pair of chamois-skin riding gauntlets exquisitely embroidered on the back with his monogram in red and white silk, made, as the giver wrote, under the guns of Fortress Monroe late at night for fear of discovery. There was a hemstitched linen handkerchief, with a little sketch in indelible ink in one corner; the children had written him little letters, their grandmother having held their hands, the burthen of which compositions was how they loved their dear father. For one of the inmates of the home, who was greatly loved but whose irritable temper was his prominent failing, there was a pretty cravat, the ends of which were embroidered, as was the fashion of the day. The pattern chosen was simple and on it was pinned a card with the word “amiable” to complete the sentence. One of the [missing] received a present of an illuminated copy of Solomon’s proverbs found in the same old store from which the pictures came. He studied it for some time and announced: “I have changed my opinion of Solomon, he uttered such unnecessary platitudes — now why should he have said ‘The foolishness of a fool is his folly’?”

On Christmas morning the children awoke early and came in to see their toys. They were followed by the negro women, who one after another “caught” us by wishing us a merry Christmas before we could say it to them, which gave them a right to a gift. Of course, there was a present for every one, small though it might be, and one who had been born and brought up at our plantation was vocal in her admiration of a gay handkerchief. As she left the room she ejaculated: “Lord knows mistress knows our insides; she jest got the very thing I wanted.”

Strange Presents

For me there were six cakes of delicious soap, made from the grease of ham boiled for a family at Farmville, a skein of exquisitely fine gray linen thread spun at home, a pincushion of some plain brown cotton material made by some poor woman and stuffed with wool from her pet sheep, and a little baby hat plaited by the orphans and presented by the industrious little pair who sewed the straw together. They pushed each other silently to speak, and at last mutely offered the hat, and considered the kiss they gave the sleeping little one ample reward for the industry and far above the fruit with which they were laden. Another present was a fine, delicate little baby frock without an inch of lace or embroidery upon it, but the delicate fabric was set with fairy stitches by the dear invalid neighbor who made it, and it was very precious in my eyes. There were also a few of Swinburne’s best songs bound in wall-paper and a chamois needle-book left for me by young Mr. P., now succeeded to his title in England. In it was a Brobdingnagian thimble “for my own finger, you know,” said the handsome, cheerful young fellow.

After breakfast, at which all the family, great and small, were present, came the walk to St. Paul’s Church. We did not use our carriage on Christmas or, if possible, to avoid it, on Sunday. The saintly Dr. Minnegerode preached a sermon on Christian love, the introit was sung by a beautiful young society woman and the angels might have joyfully listened. Our chef did wonders with the turkey and roast beef and drove the children quite out of their propriety by a spun sugar hen, life-size, on a nest full of blanc mange eggs. The mince pie and plum pudding made them feel, as one of the gentlemen laughingly remarked, “like their jackets were buttoned,” a strong description of repletion which I have never forgotten. They waited with great impatience and evident dyspeptic symptoms for the crowning amusement of the day, “the children’s tree.” My eldest boy, a chubby little fellow of seven, came to me several times to whisper: “Do you think I ought to give the orphans my I.D. studs?” When told no, he beamed with the delight of an approving conscience. All throughout the afternoon first one little head and then another popped in at the door to ask: “Isn’t it 8 o’clock yet?,” burning with impatience to see the “children’s tree.”

When at last we reached the basement of St. Paul’s Church the tree burst upon their view like the realization of Aladdin’s subterranean orchard, and they were awed by its grandeur.

Davis Plays Santa Claus

The orphans sat mute with astonishment until the opening hymn and prayer and the last amen had been said, and then they at a signal warily and slowly gathered around the tree to receive from a lovely young girl their allotted present. The different gradations from joy to ecstasy which illuminated their faces was “worth two years of peaceful life” to see. The President became so enthusiastic that he undertook to help in the distribution but worked such wild confusion giving everything asked for into their outstretched hands, that we called a halt, so he contented himself with unwinding one or two tots from a network of strung popcorn in which they had become entangled and taking off all apples he could when unobserved, and presenting them to the smaller children. When at last the house was given to the “honor girl” she moved her lips without emitting a sound, but held it close to her breast and went off in a corner to look and be glad without witnesses.

“When the lights were fled, the garlands dead, and all but we departed” we also went home to find that Gen. Lee had called in our absence, and many other people. Gen. Lee had left word that he had received a barrel of sweet potatoes for us, which had been sent to him by mistake. He did not discover the mistake until he had taken his share (a dishful) and given the rest to the soldiers! We wished it had been much more for them and him.

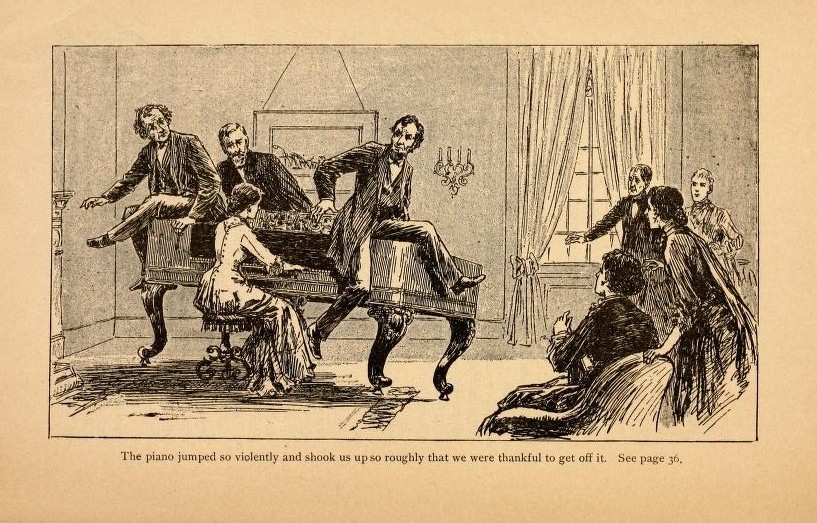

A Starvation Dance

The night closed with a “starvation” party, where there were no refreshments, at a neighboring house. The rooms lighted as well as practicable, some one willing to play dance music on the piano and plenty of young men and girls comprised the entertainment. Sam Weller’s soiry, consisting of boiled mutton and capers, would have been a royal feast in the Confederacy. The officers, who rode into town with their long cavalry boots pulled well up over their knees, but splashed up their waists, put up their horses and rushed to the places where their dress uniform suits had been left for safekeeping. They very soon emerged, however, in full toggery and entered into the pleasures of their dance with the bright-eyed girls, who many of them were fragile as fairies, but worked like peasants for their home and country. These young people are gray-haired now, but the lessons of self-denial, industry and frugality in which they became past mistresses then, have made of them the most dignified, self-reliant and tender women I have ever known — all honor to them.

So, in the interchange of the courtesies and charities of life, to which we could not add its comforts and pleasures, passed the last Christmas in the Confederate mansion.”

—Varina Davis, “Christmas in the Confederate White House,” New York Sunday World, December 13, 1896. Many former Confederates found a congenial home in New York City after the war, where they found the upper class had more in common with the former overlords of the South than the multitude of “mudsills” in the Union armies who suppressed Secessionism, saved the Nation and freed the slaves.

For more stories of the Civil War, see Ghosts and Haunts of the Civil War, and The Paranormal Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. Now in print, Ambrose Bierce and the Period of Honorable Strife, chronicles the famous American author’s wartime experiences.