Even with all the sorrow that hangs, and will forever hang, over so many households; even while war still rages; even while there are serious questions yet to be settled – ought it not to be, and is it not, a merry Christmas? Harper’s Weekly, December 26, 1863

Christmas 1863 had been a pivotal year, even if many on both sides still did not realize it. During the summer, the Federals had scored three stunning triumphs across the nation, all done at the same time. The Fourth of July 1863 witnessed the fall of Vicksburg to Grant; the defeat & retreat of Lee before Gettysburg; plus, Old Rosey had outfoxed, outmaneuvered and generally bumfuzzled General Bragg and his hard-fighting Army of Tennessee, pushing them all the way back to northern Alabama and Georgia, with only the city of Chattanooga remaining to open the door to the deep South.

But all was not lost for the Confederacy, not yet at least. The invasion of the North had not succeeded, true, but Lee withdrew in good order and the Army of Northern Virginia re-crossed the Potomac intact and ready to fight another day. In the Western Theater, Bragg retreated from Chattanooga, but the irascible and erratic Rebel general turned around and whupped Rosecrans at Chickamauga. Even the surrendered Rebel army at Vicksburg had been paroled to fight another day.

As Christmas approached, both sides shad concerns and doubts; but both sides still hoped for eventual victory. At home, meanwhile, loved ones celebrated a bittersweet Christmas as they grieved for those lost and worried for those still at the front. Soldiers far from home celebrated Christmas as best as their situation would allow. Happy were those few who were granted furlough home for the holidays; for these it was indeed a merry, even joyous, Christmas.

In East Tennessee, because the 9th Indiana had re-enlisted en masse, they were given a whole month’s leave home, with the proviso they did some recruiting to replace losses in the regiment. Their families were thus granted an extra special Christmas this year. But not every northern household was so lucky as those in northern Indiana where the men of the 9th Indiana spent the holiday. In many households the breadwinner of the family was absent from home and in some cases, not only the father, but all the sons were away as well, leaving many northern women and children to make do and the usual sweets and other gifts were not so abundant this Christmas as before. As Louis May Alcott’s heroine observes at the beginning of her classic tale about the home front during the Civil War, Little Women, “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” In the end, most households prayed that the “empty chair” would soon be occupied once more rather than pine over a lack of abundance under the Christmas tree.

As in previous wartime Christmases, the arrival of “boxes” was a much-anticipated event among troops in the field. While Christmas care boxes were important for morale among the Federals, for troops in the Confederate camp, it was sometimes ore a matter of survival. One of the many refugees from Tennessee residing in Georgia, Mrs. S.C. Law, grew concerned about the frontline Confederate troops in December of 1863 and resolved to get as many “boxes” filled with necessities to them by Christmas:

“While at Columbus, Ga., I heard of the terrible destitution of the soldiers at Dalton, Ga. in Gen. J.E. Johnston’s division. Hundreds, yes, thousands of soldiers having to sit up all night round a log fire, for want of a blanket. I was so greatly troubled to hear of the brave heroes standing like a “stone wall” between the women and children of the South and the enemy, that after a sleepless night, I went directly to a Ladies’ Aid Society, where a number of patriotic women…were at work for the soldiers. I told what I had heard of the suffering, for want of blankets by the soldiers and made an appeal to them for aid, telling them if they would furnish the blankets, I would go in person to Dalton and distribute them to the soldiers… and in one week large boxes were packed with one hundred blankets, three hundred pairs of socks, several boxes of underclothing for the needy soldiers.

….. On Christmas night I left for Dalton, accompanied by the noble, patriotic president of that Aid Society…. I then sent a note to Gen. Hardee, (Gen. Johnston being absent) telling him my mission. He came immediately. I told him I desired to go to the different commands, as I had promised the Ladies’ Aid Society to do…That evening a wagon was sent, with twenty soldiers, to receive the blankets I had brought… and I distributed blankets and clothing to those who needed them….

I then returned to Columbus, wrote and published in the papers what I had seen and heard at Dalton, of the great need of blankets for the Confederate soldiers, and made another appeal to that Ladies’ Aid Society for more blankets….The women and children worked night and day, and in ten days I returned to the army in Dalton with seven large dry goods boxes, one for Tennessee, one for Kentucky, one for Mississippi, one for Louisiana, one for Arkansas, one for Missouri, and one for Texas, all packed with five hundred and thirty blankets and coverings, and sixteen hundred pairs of socks for the soldiers…. but for the generous aid of the noble, patriotic women of Columbus, Ga. I would have been powerless to have taken those needed stores of blankets and socks to our suffering soldiers.“

For those captured at Gettysburg, their Christmas was less than a joyous one. Henry Kyd Douglas, formerly on Stonewall Jackson’s staff, had been taken during the three-day battle and was held in an overcrowded Yankee prison at Johnson Island at Christmas. The Rebel prisoners did get Christmas boxes from home, but only after their captors had inspected them to make sure the contents were “safe” to be distributed. Kyd notes in his memoirs:

“There came a carload of boxes for the prisoners about Christmas which after reasonable inspection, they were allowed to receive. My box contained more cause for merriment and speculation as to its contents than satisfaction. It had received rough treatment on its way, and a bottle of catsup had broken and its contents very generally distributed through the box. Mince pie and fruit cake saturated with tomato catsup was about as palatable as “embalmed beef” of the Cuban memory, but there were other things. Then, too, a friend had sent me in a package a bottle of old brandy. On Christmas morning I quietly called several comrades up to my bunk to taste the precious fluid of…DISAPPOINTMENT! The bottle had been opened outside, the brandy taken and replaced with water, adroitly recorded, and sent in. I hope the Yankee who played that practical joke lived to repent it and was shot before the war ended.….”

Lt. Colonel Frederic Cavada, of the 114th Pennsylvania, was also captured at Gettysburg but by the opposite side. He found Christmas at Richmond’s Libby Prison equally, if not more, dismal a holiday destination. He tells us that, “The north wind comes reeling in fitful gushes through the iron bars and jingles a sleigh-bell in the prisoner’s ear, and puffs in his pale face with a breath suggestively odorous of eggnog.” The colonel and his fellow prisoner improvised a Christmas supper of sorts, with a tea-towel for their tablecloth over a wooden box. The inmates even put on a Christmas Ball, of sorts, with a great deal of “bad dancing” in torn uniforms. Cavada closes his memoir of Christmas 1863 with the note, “Christmas Day! A day which was made for smiles, not sighs – for laughter, not tears – for the hearth, not prison.”

For civilians in the South, Christmas of 1863 was far less joyous than ever before, with the Union naval blockade beginning to have its effect. Many items that had been standard fare had to be substituted with something else – “ersatz”– such as chicory and roasted grain for coffee (and if you have ever tasted chicory tea you know how awful it can be); trees were trimmed with pig’s ears and tails instead of candy canes and small presents and mothers tried to improvise gifts as best they could. Many children went without anything at all, and all their heartbroken mothers could say to them was that “Santa couldn’t get through the blockade.”

In the White House during the Lincoln years, like many northern households, there was no Christmas Tree in evidence. Nonetheless, the Lincoln family observed the holiday in a manner that would have done Charles Dickens proud. Earlier in the war, Mary visited the hospitals at Christmas to tend to the wounded; she also raised thousands of dollars to provide Christmas Dinner for those without and similarly raised money to provide oranges and lemons for the soldiers when she heard of the danger of scurvy among the troops, whose regular military rations lacked such amenities. Mary went about all such charitable work quietly and without any fanfare, even as her many detractors North and South labeled her as vain and selfish.

During Christmas of 1863, young Tad Lincoln accompanied his father to visit the wounded soldiers in the hospitals in Washington. Tad could not help but notice how sad and lonely many of the young soldiers looked. Tad had been fond of dressing up like a soldier in the white house, even getting hold of an old musket once, and so he closely identified with the wounded warriors he saw. He prevailed on his father that he might send them books and clothing for Christmas, and Lincoln agreed. Soldiers in the hospitals in the Washington area that Yuletide received presents signed, “From Tad Lincoln.”

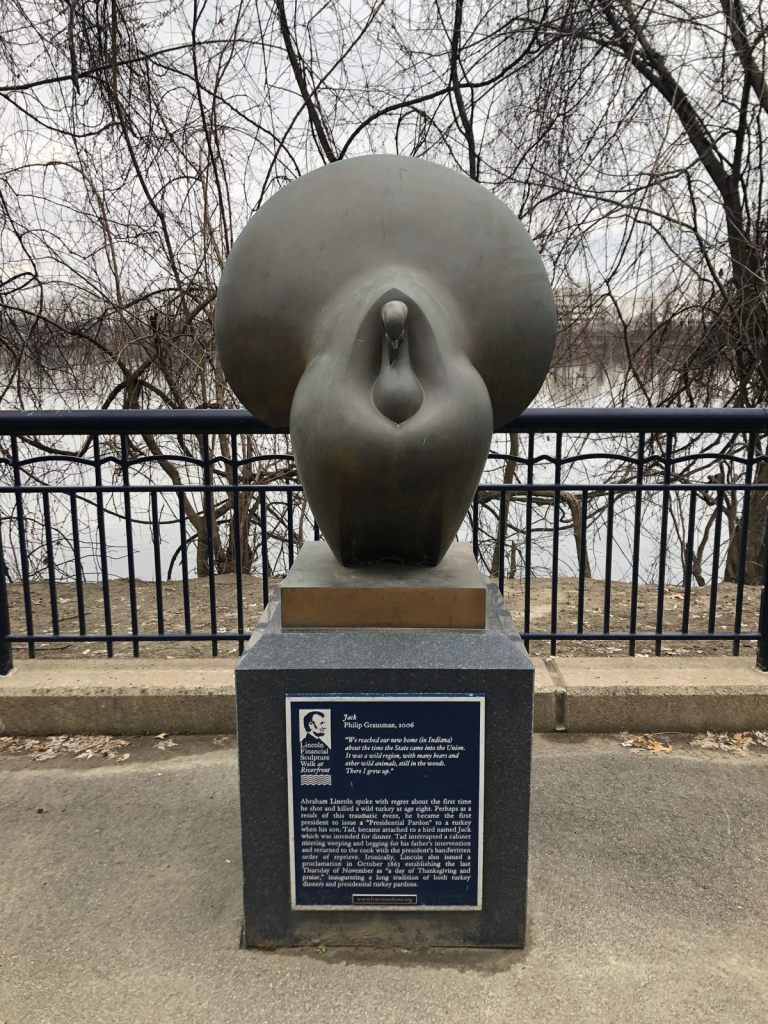

Young Tad also started a holiday tradition which is still observed to this day. Tad befriended a turkey that was being fattened for Christmas Dinner, nicknaming him “Jack.” When the lad learned the fate that awaited Jack, Tad burst into a cabinet meeting to plead with his father to spare Jack’s life.

Most fathers of that day would have rewarded their son with a whipping for breaking in on an important business meeting, but Lincoln was more indulgent than most, especially after losing his middle son Willie to a fever. President Lincoln therefore drew up a formal pardon and officially signed it, sparing Jack’s turkey neck to gobble for another year.

Young Tad was a precocious lad and at times a handful for the staff in the White House; yet he had his father’s great heart and an empathy for others. Had he survived to adulthood he may well have followed in this father’s steps.

While he never uttered the words of Dickens’ Tiny Tim, one could well imagine the precocious young Tad Lincoln bursting out that Christmas of ’63 at dinner: “God Bless Us Everyone!”

For more about Lincoln and his family, see The Paranormal Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, and for curious lore about the Civil War, read Ghosts and Haunts of the Civil War. Now in print is Ambrose Bierce and the Period of Honorable Strife, about the famous author and his service in the Civil War.