William Henry Seward, born 119 years ago, May 16, 1801, was a man whose life was one of service, not only to the people who elected him to various offices, and later as a cabinet officer to one of our greatest presidents, but to the advancement of human rights for his state and the nation.

Seward is best known as Lincoln’s Secretary of State during the Civil War, during which time he proved of great service to Lincoln and the nation. While that was the period of his greatest achievements in the area of diplomacy, he is best known for the purchase of Alaska from Imperial Russia in 1867, which a hostile press dubbed “Seward’s Folly.”

Prior to the war, Seward had had a long political career in New York state, serving in various capacities, during which he developed a reputation as being a strong advocate of immigrants’ rights, public education, prison reform, humane treatment of the insane, racial equality, religious toleration and human rights in general.

In a famous trial, Seward defended a man, William Freeman, accused of murdering four people in an unprovoked act. Freeman was not only guilty of that crime, but was guilty of being Black, which many at the time considered a far worse offense. Knowing Freeman was insane, Seward felt he should not be given the death penalty and agreed to defend him, even though it seemed a lost cause. Seward argued eloquently for leniency, giving the justification that he was not guilty by reason of insanity, an early use of that defense in a court of law. While Seward was unable to get the man acquitted, but he did prevent him from being executed, this in a period where even in the North Blacks were unlikely to get a fair trial. In summing up his case before the jury Seward argued, “he is still your brother, and mine, in form and color accepted and approved by his Father, and yours, and mine, and bears equally with us the proudest inheritance of our race—the image of our Maker. Hold him then to be a Man.”

Nor was this an isolated example of Seward’s fight for human rights. As governor Seward signed several laws which advanced the rights and opportunities of Blacks in New York, and sought to protect fugitive slaves to the best of his ability in the various state offices he held. Seward was not an Abolitionist, per se since he believed in gradual emancipation as the way to end slavery; but in all other aspects his beliefs were in accord with the Abolitionists and indeed in a broad spectrum of civil rights and reforms. It is also believed that his home in upstate New York served as a station on the “Underground Railroad.”

Throughout its existence, Seward was active in the Whig Party, which was the first political party to believe in legislative action to develop the nation. Their strong advocacy of using the Federal government to intervene in what had before been the strict domain of the private sector, has led some political analysts to label the Whig Party as America’s first Socialist Party, although many would dispute that view. Certainly, Seward was among the more activist of the Whigs promoting civil rights, universal public education and land reform, as well as national expansion and economic growth.

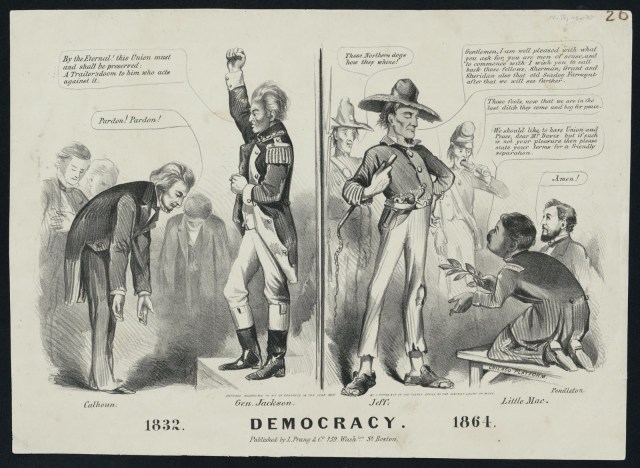

When the Whig Party fell apart due to internal divisions over slavery, Seward gravitated towards the new Republican Party, whose rank and file included quite a number of genuine Socialists, and there is no question that from its beginning, the party was strongly imbued with Socialist ideals, as strange as that may seem today. In the mid nineteenth century, political reform movements had two main strains; one were the Liberals, who believed in Laissez Faire economics coupled with a small central government with only very weak powers; and the Socialists, who generally advocated a strong role for government to both expand human rights and economic justice, and also to promote national development. While Seward’s own political philosophy was less ideological than many of his fellow Republicans who were Socialists, in practical terms his political views on specific issues were very much in line with theirs. As the issue of slavery became more and more contentious in the Senate, Seward incurred the wrath of its advocates for his warnings about the inevitability of Slavery’s demise, although on a personal level he had cordial relations with some of the less fanatic members of the Slaveocracy, such as Jefferson Davis.

During the 1858 mid-term elections Seward made a speech in Rochester, New York, which became famous (or infamous, depending on one’s political views). He pointed out that the U.S. had two, “antagonistic system [that] are continually coming into closer contact, and collision results … It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become entirely either a slave-holding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation.”

To Seward, this speech was simply stating the obvious; to Secessionists, the speech was considered a provocation and yet another justification for their growing militancy on the issue of slavery.

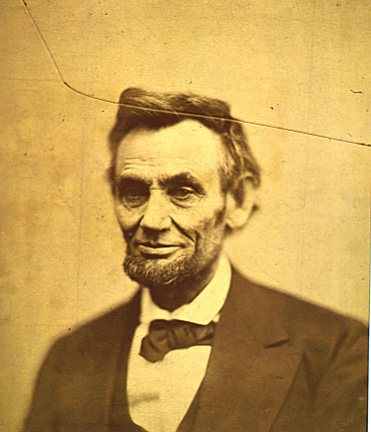

As the 1860 presidential election approached, Seward seemed the leading candidate for the Republican nomination. However, his vocal opposition to slavery, his support for immigrants and Catholics, and his association with political boss Thurlow Weed all worked against him, and Abraham Lincoln secured the presidential nomination instead. Although disappointed, Seward campaigned tirelessly for Lincoln, who appointed him Secretary of State after winning the election.

Although Seward tried to prevent the southern states from seceding, when those efforts failed, he devoted himself wholeheartedly to the Union cause. Most notable during his tenure as Secretary of State, were his efforts to prevent foreign intervention in the Civil War.

Both Britain and France were eager to help the cotton growing Southern states in their rebellion, with a view to eventually turning the South into an economic fiefdom of their growing Capitalist industries. One way he did this was by cultivating the friendship of both Prussia and Russia. At one point during the war, the Czar made a point of sending both his Atlantic and Pacific fleets on a friendly visit to the United States, where the Secretary of State made sure they were warmly welcomed. This show of military might was not lost on the His Majesty’s government in London, who understood that intervening on behalf of the Confederacy would have consequences in Europe as well as America. The close relations Seward cultivated with Russia during the war would later be helpful a few years later in obtaining Alaska from the Czarist government on very reasonable terms.

On the night Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, Seward himself barely escaped death at one of the conspirator’s hands.

Seward stayed on into the Johnson Administration and not only secured the vast natural resources of Alaska but was also instrumental in forcing the French to withdraw from Mexico in 1866; at one point he expressed interest in also obtaining Cuba from the Spanish, but that effort found little support, either at home or abroad.

His contemporary, Republican and Socialist Carl Schurz described Seward as “one of those spirits who sometimes will go ahead of public opinion instead of tamely following its footprints.” His role in helping Lincoln in the war, and America in peace, is today perhaps largely forgotten, his achievements were nonetheless of lasting importance and deserve to be remembered.

For more about Lincoln and his administration, read The Paranormal Presidency of Abraham Lincoln published by Schiffer Books; for an in depth look at one man’s participation in the Civil War, look up Ambrose Bierce and the Period of Honorable Strife.

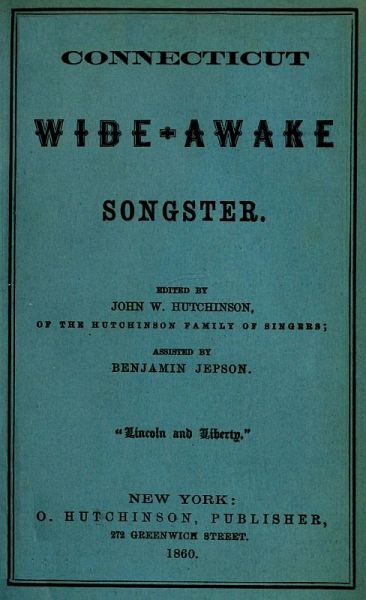

The Hutchinsons worked very hard for the Lincoln Campaign. John Hutchinson compiled two campaign songbooks t

The Hutchinsons worked very hard for the Lincoln Campaign. John Hutchinson compiled two campaign songbooks t