In 1895, Stephen Crane coined the phrase “red badge of courage” to describe wounds that soldiers received in battle during the Civil War. Truth be told, more soldiers died of disease and other causes than as a result of actual combat wounds. To be wounded or to die in heat of battle was viewed as far more heroic than soldiers falling ill with Typhus, Malaria, Dysentery or other common diseases of war. All those who fell ill and who died on campaign suffered serving in the line of duty; by rights, how they became incapacitated or died should not matter. But nineteenth century notions of manliness and honor colored much of the thinking with regard to suffering and death during the war.

As with so many other things, the Civil War was a watershed period in the medical treatment of combat casualties and wartime wounded. By the standards of just a few years later, the treatment of the sick seemed primitive, barbaric even. But out of this initial chaos, doctors and nurses, and the institutions that oversaw the care for sick and wounded soldiers made great advances in care and treatment.

In earlier wars, treatment of the wounded was not the concern of the armies and governments who sent them off to war. More often than not, if a soldier suffered a wound and survived, his treatment was in the hands of his “camp follower”–his common-law wife or mistress who, with thousands of others, followed in the wake of the marching armies. The philosophy of “laissez-faire” government extended not just to economics but even to their own soldier’s well-being. A smart uniform, functioning equipment, bad food and meagre pay were the limits of a governments’ obligation to its soldiers–and sometimes not even that.

To be sure, during the latter part of the 18th century, armies began to have physicians attached to regiments and larger units, more for morale purposes, one suspects, than for any deep concern for the cannon fodder that fought for the European, and later American, states as they emerged from Medieval times to a supposedly more “enlightened” era.

But up until the Civil War, save for a few exceptions, most wars were fought on a much smaller scale, with the numbers of dead surprisingly small, and the wounds inflicted on the participants, while painful and often ghastly to behold, less fatal than one might suppose. Disease and malnutrition killed far more soldiers than battlefield wounds.

As nations became more “civilized” and technologically advanced, however, weapons too became more advanced-and more lethal. Save but for the Napoleonic Wars, the American Civil War was fought on a scale unimaginable to most modern nations and their leaders and soon the number of men needing immediate medical care could be counted not in the hundreds, but thousands, and at times tens of thousands.

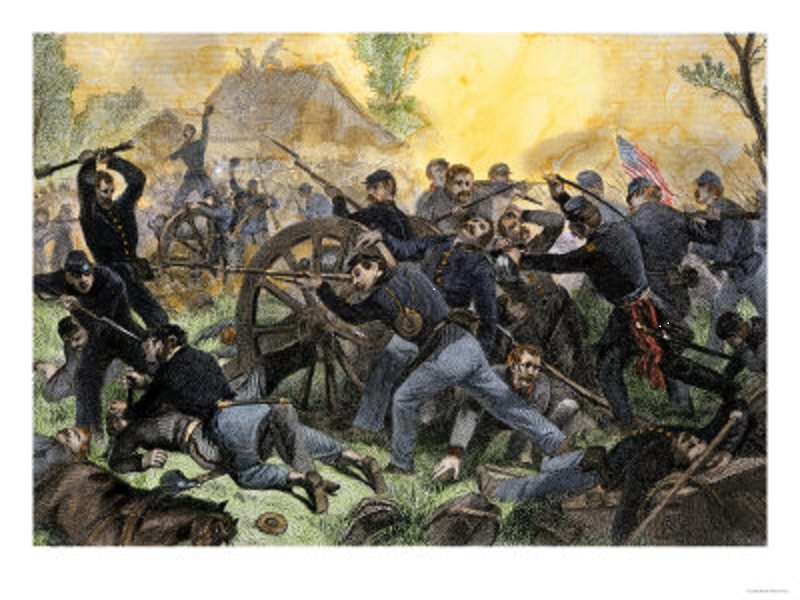

The Union and Confederate armies had been in a deadly contest for nearly a year when both sides met by the banks of the Tennessee River on Easter Sunday of 1862 near a small rural church whose name meant “peace.” The level of bloodletting that April 6, 1862, was on a scale that shocked even the most hardened of warriors and forever labeled that two-day conflict as “Bloody Shiloh.”

We cannot hope in this limited venue to describe the all aspects of the care of the wounded at Bloody Shiloh and its immediate aftermath, much less the changes which the war wrought to medicine and combat surgery. So we shall have it chronicled by one lone voice, a man who was in the very center of the carnage and did his utmost to save the lives of as many American soldiers, regardless of whether they wore blue or grey, those terrible two days in April.

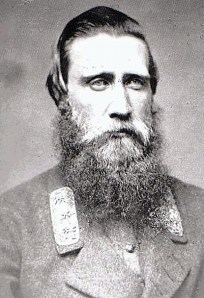

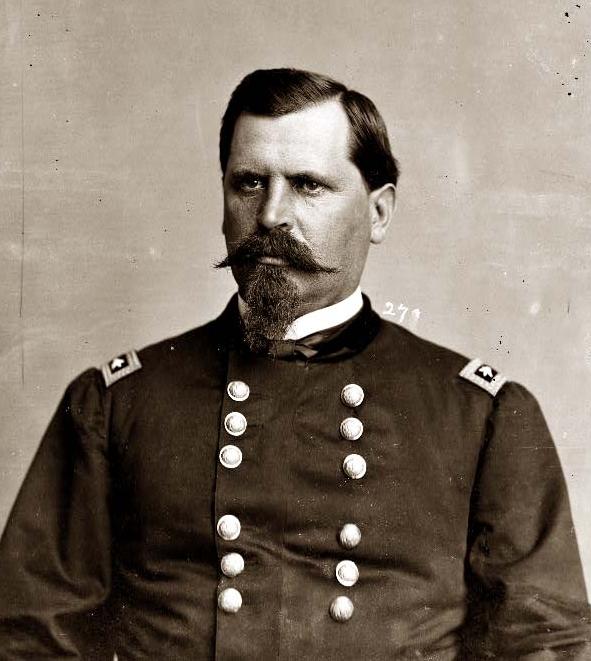

At the time of the Battle of Shiloh, Major Robert Murray was Medical Director for the Army of the Ohio, under General Don Carlos Buell. Most of Buell’s troops did arrive until after dark on the sixth; but they got in position overnight and on the next day were the main force which counter-attacked the Rebel Army, turning defeat into victory. By far, most of the Union casualties were from Grant’s army who, though warned, was still taken by surprise on the sixth and his forces driven back and demoralized by the large Rebel force.

Major Murray was originally from the border state of Maryland and while he served loyally in the Union Army, two of his brothers fought in the Confederate Army. What follows is his report on the medical services under his command at Shiloh, published in the OR, the massive publications of the records of the Union and Confederate armies.

MEDICAL DIRECTOR’S OFFICE, ARMY OF THE OHIO,

Camp on Field of Shiloh, April 21, 1862.

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the operations of the medical department during and after the battle of the 6th and 7th instant:

On the morning of the 6th I was at Savannah, and being ordered to remain at that place, I occupied myself in procuring all the hospital accommodation possible in that small village and in directing the preparation of bunks and other conveniences for wounded. In the afternoon the wounded were brought down in large numbers, and I then superintended their removal to hospitals, and did all in my power to provide for their comfort. On Sunday evening, the divisions being under orders to come up as rapidly as possible, I ordered the medical officers, as it was impossible to take their medical and hospital supplies — the teams and ambulances being in the rear and the roads blocked up with trains — to take their instruments and hospital knapsacks and such dressings and stimulants as could be carried on horseback, and to go on with their regiments.

I left Savannah by the first boat on Monday, and arrived at Pittsburg Landing at about 10 a.m. I found the principal depot for wounded established at the small log building now used as a field post-office. They were coming in very rapidly, and very inadequate arrangements had been made for their reception. I found Brigade Surgeon Goldsmith endeavoring to make provision for them, and at his suggestion immediately saw General Grant, and obtained his order for a number of tents to be pitched about the log house.

I then rode to the front and reported to you. The great number of wounded which I saw being transported to the main depot, and the Almost insurmountable difficulties which I foresaw would exist in providing for them, convinced me that my presence was needed there more than at any other point on the field. After spending an hour in riding a little to the rear of our lines, and seeing as far as possible that there were surgeons in position to attend immediately to the most urgent cases, I returned to the hill above the Landing, and used every exertion to provide for the wounded there. I ordered Brigade Surgeons Gross, Goldsmith, Johnson, and Gay to take charge of the different depots which were established in tents on the hills above the Landing, directing such regimental and contract surgeons as I could find to aid them.

Many of the wounded were taken on board boats at the Landing and some of our surgeons were ordered on board to attend them. On Tuesday I had such beats as I could obtain possession of fitted up with such bed-sacks as were on hand and with straw and hay for the wounded to lie upon, and filled to their utmost capacity, and at once dispatched to convey the worst cases to the hospitals on the Ohio River, at Evansville, New Albany, Louisville, and Cincinnati.

In removing the wounded we were aided by boats fitted up by sanitary commissions and soldiers’ relief societies and sent to the battle-field to convey wounded to the hospitals. Some of these, especially those under the direction of the United States Sanitary Commission, were of great service. They were ready to receive all sick and wounded, without regard to States or even to politics, taking the wounded Confederates as willingly as our own. Others, especially those who came under the orders of Governors of States, were of little assistance, and caused much irregularity. Messages were sent to the regiments that a boat was at the Landing ready to take to their homes all wounded and sick from certain States. The men would crowd in numbers to the Landing, a few wounded, but mostly the sick and homesick. After the men had been enticed to the river and were lying in the mud in front of the boats it was determined in one instance by the Governor to take only the wounded, and this boat went off with a few wounded, leaving many very sick men to get back to their camps as they best could. By the end of the week after the battle all our wounded had been sent off, with but few exceptions of men who had been taken to camps of regiments in General Grant’s army during the battle. These have since been found and provided for.

The division medical directors were very efficient in the discharge of their duties, and they report most favorably of the energy and zeal displayed by the medical officers under them in the care of the wounded under most trying circumstances — of want of medical and hospital stores, and even tents. Owing to the fact that a large majority of the wounded brought in on Monday and Tuesday were from General Grant’s army, some of whom had been wounded the day before, it was impossible to attend particularly to those from our own divisions. Many Confederate wounded also fell in our hands, and I am happy to say that our officers and men attended with equal assiduity to all. Indeed, our soldiers were more ready to wait on the wounded of the enemy than our own. I regret to say that they showed incredible apathy and repugnance to nursing or attending to the wants of their wounded comrades, but in the case of the Confederates this seemed in some measure overcome by a feeling of curiosity and a wish to be near them and converse with them.

We were poorly supplied with dressings and comforts for the wounded and with ambulances for their transportation, and it was several days after the battle before all could be brought in. Our principal difficulty, however, in providing for the wounded was in the utter impossibility to obtain proper details of men to nurse them and to cook and attend generally to their wants, and in the impossibility of getting a sufficient number of tents pitched, or in the confusion which prevailed during and after the battle to get hay or straw as bedding for the wounded or to have it transported to the tents. The only details we could obtain were from the disorganized mob which lined the hills near the Landing, and who were utterly inert and inefficient. From the sad experience of this battle and the recollections of the sufferings of thousands of poor wounded soldiers crowded into tents on the wet ground, their wants partially attended to by an unwilling and forced detail of panic-stricken deserters from the battle-field, I am confirmed in the belief of the absolute necessity for a class of hospital attendants, enlisted as such, whose duties are distinct and exclusive as nurses and attendants for the sick, and also of a corps of medical purveyors, to act not only in supplying medicines, but as quartermasters for the medical department.

I append a list of the number of killed and wounded in each regiment, brigade, and division engaged, in all amounting to 236 killed and 1,728 wounded.(*)

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

R. MURRAY,

Surgeon, U. S. Army, Medical Director.

Col. J. B. FRY,

Asst. Adjt. Gen. and Chief of Staff, Army of Ohio.

*Major Murray’s figures are way off, but he may only be counting Buell’s casualties, mostly received on the second day. Best estimate is that Union losses were 1754 killed, 8408 wounded, and 2885 captured: total, 13,047–of which only about 2,000 were Buell’s men.