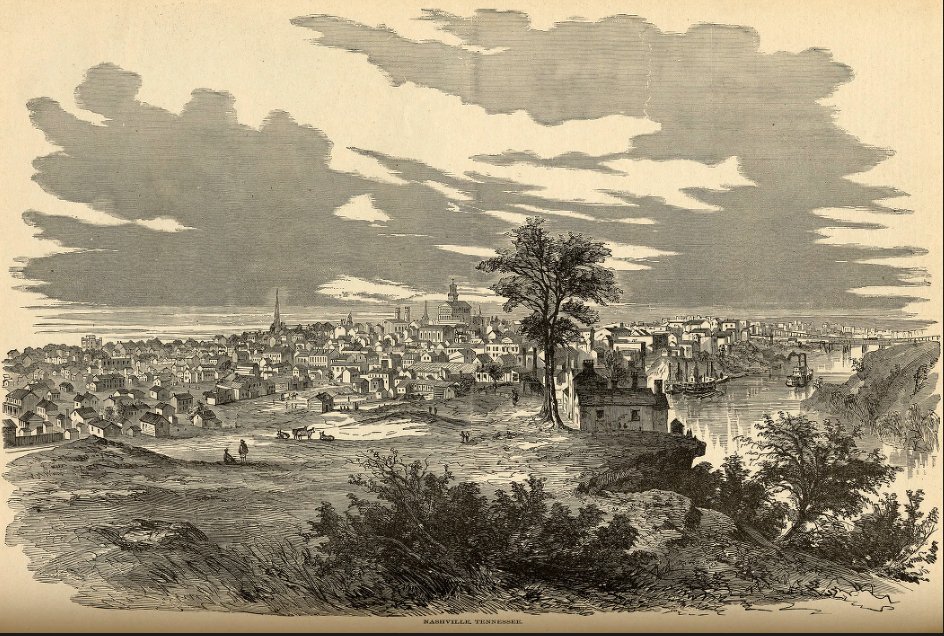

On February 25, 1862, the city of Nashville fell to the Union Army of the Ohio. In the aftermath of Grant’s famous victory at Forts Donelson and Henry, the importance of this event has tended to be overlooked by history (and of course, historians), but the significance of the capture of the Confederate Capitol cannot be underestimated.

As James Lee McDonough noted in his 1977 book on Shiloh, when the Federals occupied Nashville, it was not simply the first Rebel state capitol to fall, it also meant the capture of a major Confederate industrial center and transportation hub. Much as they do today, a number of roads and pikes plus five railroads lines radiated out in all directions; moreover, in the 1860’s river transportation was far more important than now and the Cumberland linked Nashville and the Confederate heartland to the Ohio Valley in one direction and East Tennessee and eastern Kentucky in the other.

Just as importantly, Nashville and Middle Tennessee was an important manufacturing center which was now denied the Confederate war machine. The iron industry in Middle Tennessee dated back to frontier days and the steady flow of the Cumberland River powered any number of mills and factories. There were cannon foundries, small arms manufacturers, while the caves in the surrounding region supplied saltpeter for the manufacture of gunpowder and the fertile farmlands of the region provided food and livestock in quantities enough to supply an army. In addition, there was the Nashville Armory, located on College Hill, just south of the town, where large stands of arms and ammunition were stored; several steamboats were also in the process of being converted to gunboats to counter the Yankee war machines. All these strategic assets would now be denied the Confederacy for the duration of the war. From Nashville too, Union troops would sally forth in all directions to subdue the Rebellion over the next several years, with ample supplies to sustain them. No one realized it at the time, but the fall of Fort Donelson and the capture of Nashville spelled the doom of the western Confederacy—and ultimately of the Rebellion as a whole.

In the ten days following Grants victory at Land Between the Rivers (today Land Between the Lakes) the remnants of Confederate forces not caught in the surrender came reeling southward toward “Rock City” (as Nashville was nicknamed), the Secessionist state government made haste to high tail it out of town and a general panic ensued among the civilian population. This was the general situation on February 25, 1862, as exemplified by a diary entry at the time:

Today it seems settled that we met with a disastrous defeat in the end at Donelson by the enemys overpowering numbers surrounding our men, who fought bravely & well. Gens. Floyd & Pillow escaped with some of the troops__ but Buckner is a prisoner. It is now contradicted that Nashville surrendered, & sent a boat with a flag of truce down the Cumberland to meet the enemy & give up the city (!) as was at first reported__ but it is certain that our troops from Bowling Green have fallen back to Murfreesboro and they have burnt the bridges, steamboats etc. at Nashville and not a Yankee near them! Oh! it is disgraceful! Gov. Harris who rode round town alarming the citizens__ who said to Ewing__ Every man must now take care of himself; I am going to take care of myself__ fled. Lucy French Diary (courtesy TSLA)

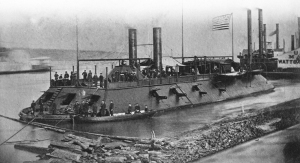

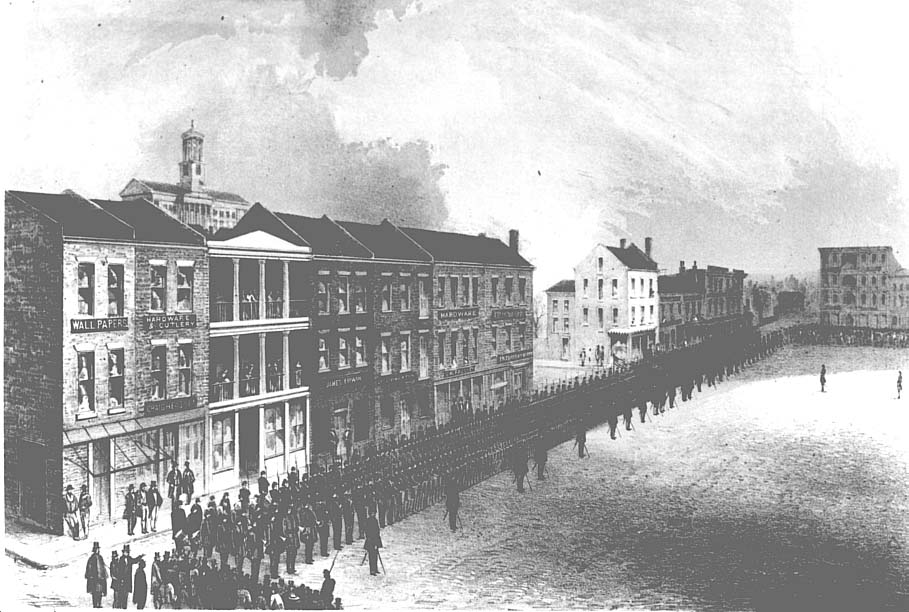

Imagine, if you will, how the remaining citizens of the City felt when they awoke that morning to see an ominous looking tortoise-shaped gunboat sitting on the opposite bank with massive guns pointed directly at them. In fact, the mayor of Nashville the day before had already arranged for the peaceful occupation of the city with General Buell, the Union army commander. However, General “Bull” Nelson jumped the gun a bit and that Sunday morning began unloading his troops first thing, before the formal surrender. General William B. Hazen’s 19th Brigade was one of the first to debark marching along Lower Broadway for a few blocks before wheeling right to ascend the steep acclivity towards the state capitol.

Hazen halted in front of the St. Cloud Hotel, now an office building at the corner of Fifth and Church Streets, where he was met by the proprietor of the hotel, Mr. Carter, who invited Hazen and his staff into his “scanty bar.” The innkeeper was solicitous of his new guests and Hazen, a teetotaler, tells us Carter tasted everything first, “to assure us.” Of the previous guests of the St. Cloud, Hazen tells us “we found in the hotel, fast asleep and very drunk, one Rebel soldier, the largest man I ever saw in uniform.” The bar on the ground floor of the hotel soon became a favorite watering hole of Union officers and the hotel became General Buell’s temporary headquarters.

Of those Nashville’s citizens who had not fled in the panic of the previous week, some had turned out to watch the arrival of the Yankees. But it was not a cheering or welcoming crowd, as the Union regiments had experienced when they had marched off to war. Rather, for those brave enough to venture onto the street, it was more a somber, perhaps even morbid, gathering; more like the sort of crowd which gathers to witness the aftermath of a terrible accident in the street: a sight terrible to behold, but too compelling to turn away from.

It was a somber Sunday for the denizens of the Rebel capital—except for one man. William Driver was a retired Yankee sea captain, who had moved to Nashville years before to enjoy the city’s Southern charm. A devoted patriot, loyal to the Union, when the city caught Secessionist fever, Captain Driver proved immune to the disease and instead flew the stars and stripes—the banner he had flown while at sea–proudly outside of his home, and which he had nicknamed “Old Glory.” As Driver later explained, “it has ever been my staunch companion and protection. Savages and heathens, lowly and oppressed, hailed and welcomed it at the far end of the wide world. Then, why should it not be called Old Glory?”

As the Southern states seceded one by one, his neighbors became progressively more hostile to the old sea captain. Some threatened to rip the flag down and burn it; others hinted more darkly that the Yankee captain should be hung by it. To prevent the beloed flag being desecrated, Captain Driver finally took down it down, folded Old Glory very carefully, and had it sewn into a quilt.

That Sunday morning, from his house on Rutledge Hill, Driver could see the Federals unloading from their armed transport. He hastened upstairs and retrieved the bed-quilt from its hiding place and made his way down to Lower Broad and then on up opposing hill all the way up to the state capitol building. In contrast to his fellow citizens, Captain Driver was in a jubilant mood as he mingled with the blue-clad troops.

Horace Fisher, General Nelson’s aide-de-camp, witnessed what happened next:

“A stout, middle-aged man, with hair well shot with gray, short in stature, broad in shoulder, and with a roll in his gait, came forward and asked, ‘Who is the General in command? I wish to see him.’” Driver briefly conferred with the six foot tall general—who himself had formerly been a Navy man—and, “when satisfied that Gen. Nelson was the officer in command, he pulled out his jack-knife and began to rip open the bedquilt without another word. We were puzzled to think what his conduct meant….the bedquilt was safely delivered of a large American flag, which he handed to Gen. Nelson, saying, ‘This is the flag I hope to see hoisted on that flagstaff in place of the damned Confederate flag set there by that damned rebel governor, Isham G. Harris. I have had hard work to save it; my house has been searched for it more than once.’ He spoke triumphantly, with tears in his eyes.”

Nelson accepted the flag and immediately ordered it run up on the Capitol flagstaff, accompanied by “frantic cheering and uproarious demonstrations.” The mission of climbing to the top of the state building was tasked to men of the 6th Ohio Infantry who double-timed it up the capitol steps, into the bowels of the abandoned building and up into the glass-framed cupola on top of the classical styled building.

According to local tradition, the erection of Old Glory from the flagstaff was not without incident. A former state legislator and fire-breathing Secessionist, who had not fled with the rest when Fort Donelson fell, stood on the narrow wrought iron spiral staircase with musket in hand, blocking their way.

“You’ll raise that rag over this building over my dead body!” the greybeard Rebel told the flag detail.

The officer in charge was about to issue the militant Secesh a warning, when a shot rang out from behind, hitting the Rebel in the breast. He died almost instantly, his limp body tumbling down the spiral staircase past them.

The men of the color guard continued their ascent and as the growing crowd of Federals outside witnessed the large banner unfurl, were met with resounding cheers as the flag ascended to the pinnacle of the highest spot in the city. For ever after, the 6th Ohio would be nicknamed the “Old Glory” regiment.

The sun went down that Sunday on the American flag once more flying over the capital of Tennessee and a growing army of blue spreading out through Nashville and its surrounding territory.

It was by no means the beginning of the end for the Rebellion, but to borrow a phrase from Sir Winston Churchill, it was very much the end of the beginning. From now on, the Confederacy would be fighting for its survival.

For more on the Civil War, see The Paranormal Presidency of Abraham Lincoln and Ghosts & Haunts of the Civil War.